As I write the United Kingdom is in lockdown. My diary, previously filling up with community workshops, performances and gatherings is reconfiguring into online classes, phone calls and a lot of empty spaces. Over the last year my way of working has begun to shift – I have often worked in solitude but now I feel lucky to have begun to collaborate, co-teach and to have started conversations with other artists, educators and writers. The effects of this physical distance from others feels particularly heightened when seen in the context of the community that has started to form around me.

April 15th marks the day when myself and artist Lydia Beilby were scheduled to perform a new version of Celluloid at the Edinburgh Science Festival. This was to be the first time that Lydia and I would perform together – me as storyteller, Lydia as film maker and projectionist. As many good things begin, we were introduced by a friend, who noticed an affinity in our work. When I first wrote Celluloid I became fascinated by the materiality of film: its strength and counterpart fragility, the way in which the hands that held it left a mark on the surface. Lydia brought with her not only technical knowledge of working with analogue film but a deep understanding of the unique artistic qualities of the medium. Whilst sitting and watching a selection of Lydia's films, in particular her work with archive footage it became clear that introducing this new element to the performance would create a rich, multi-faceted experience for the audience.

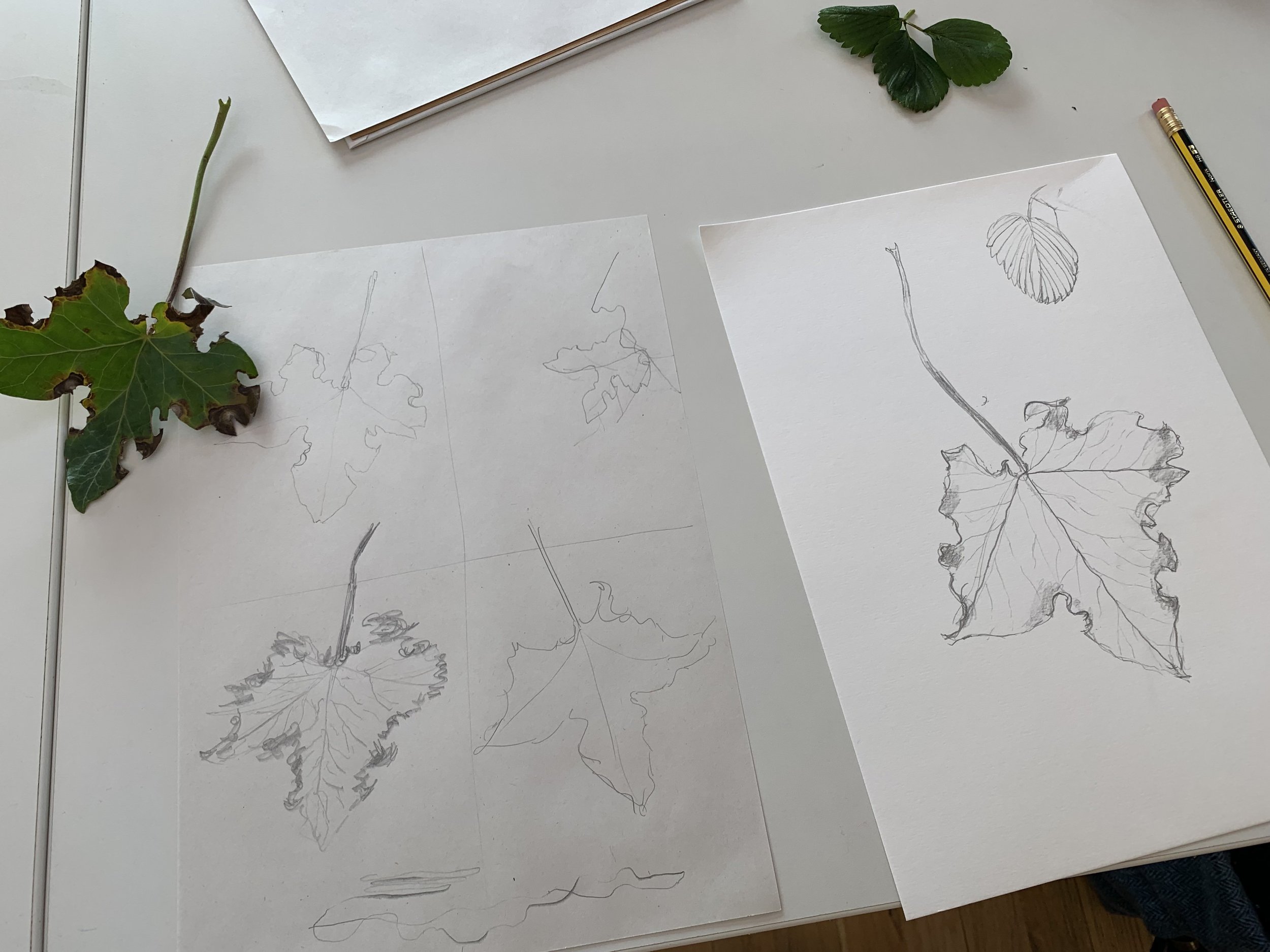

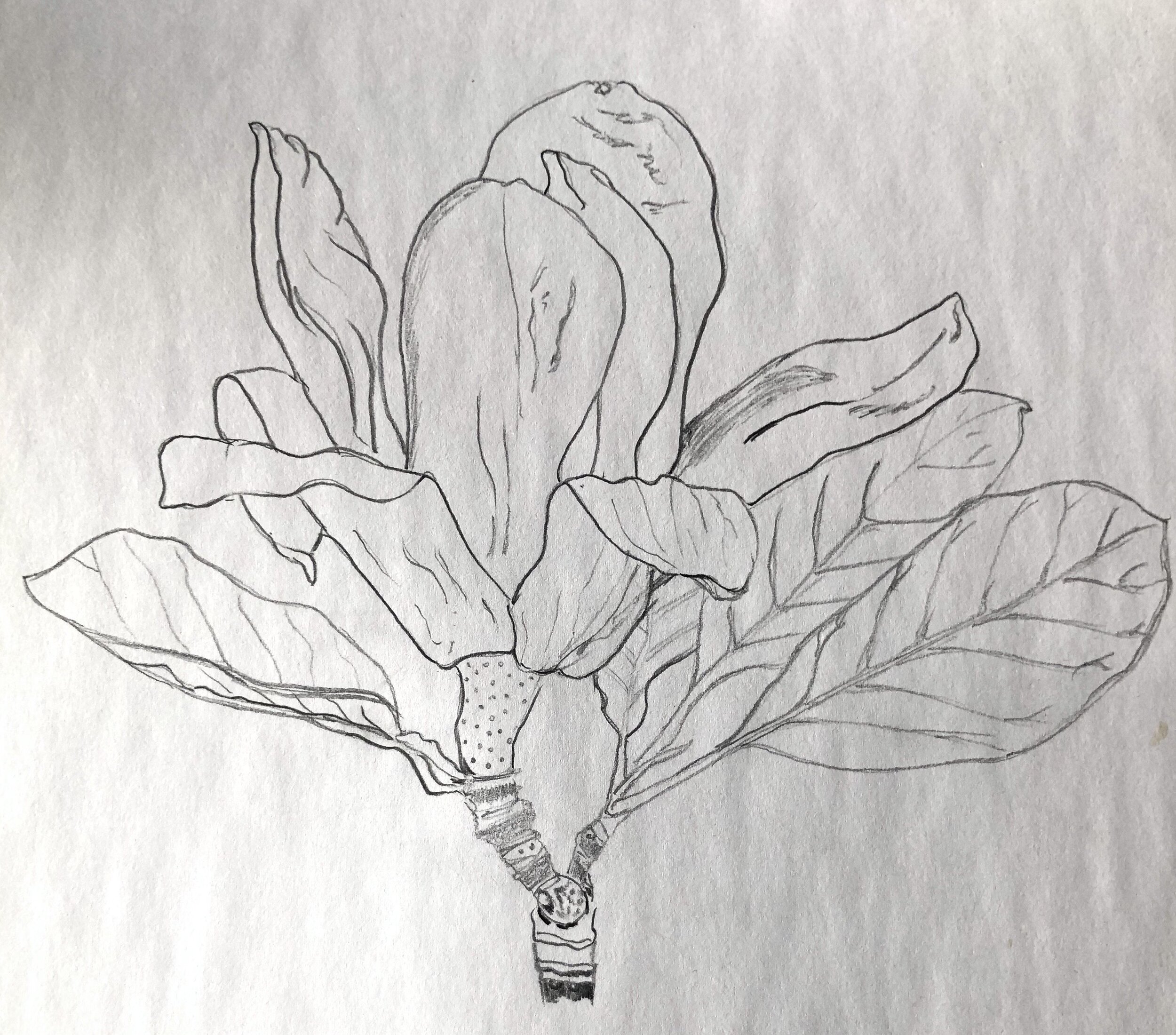

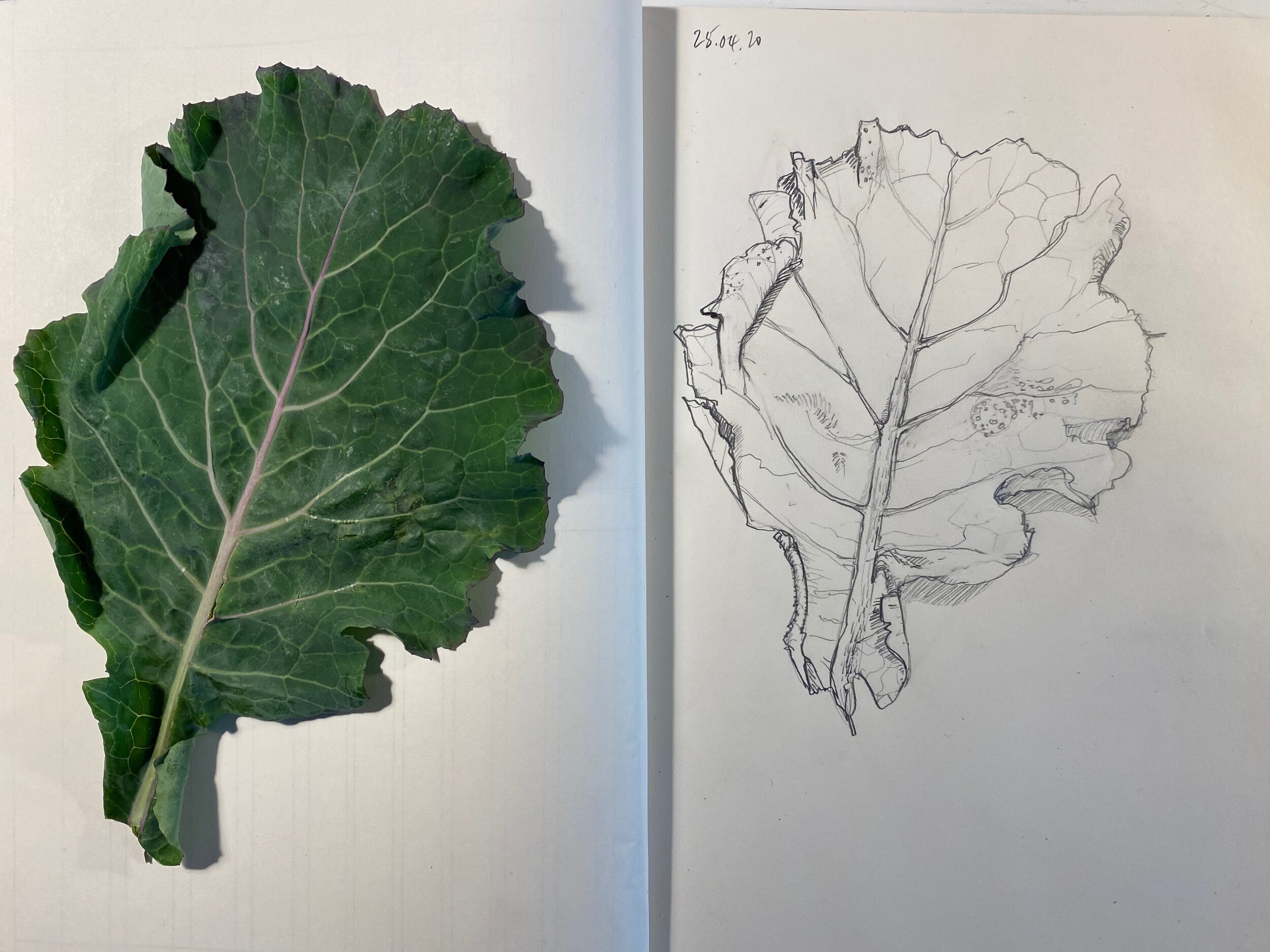

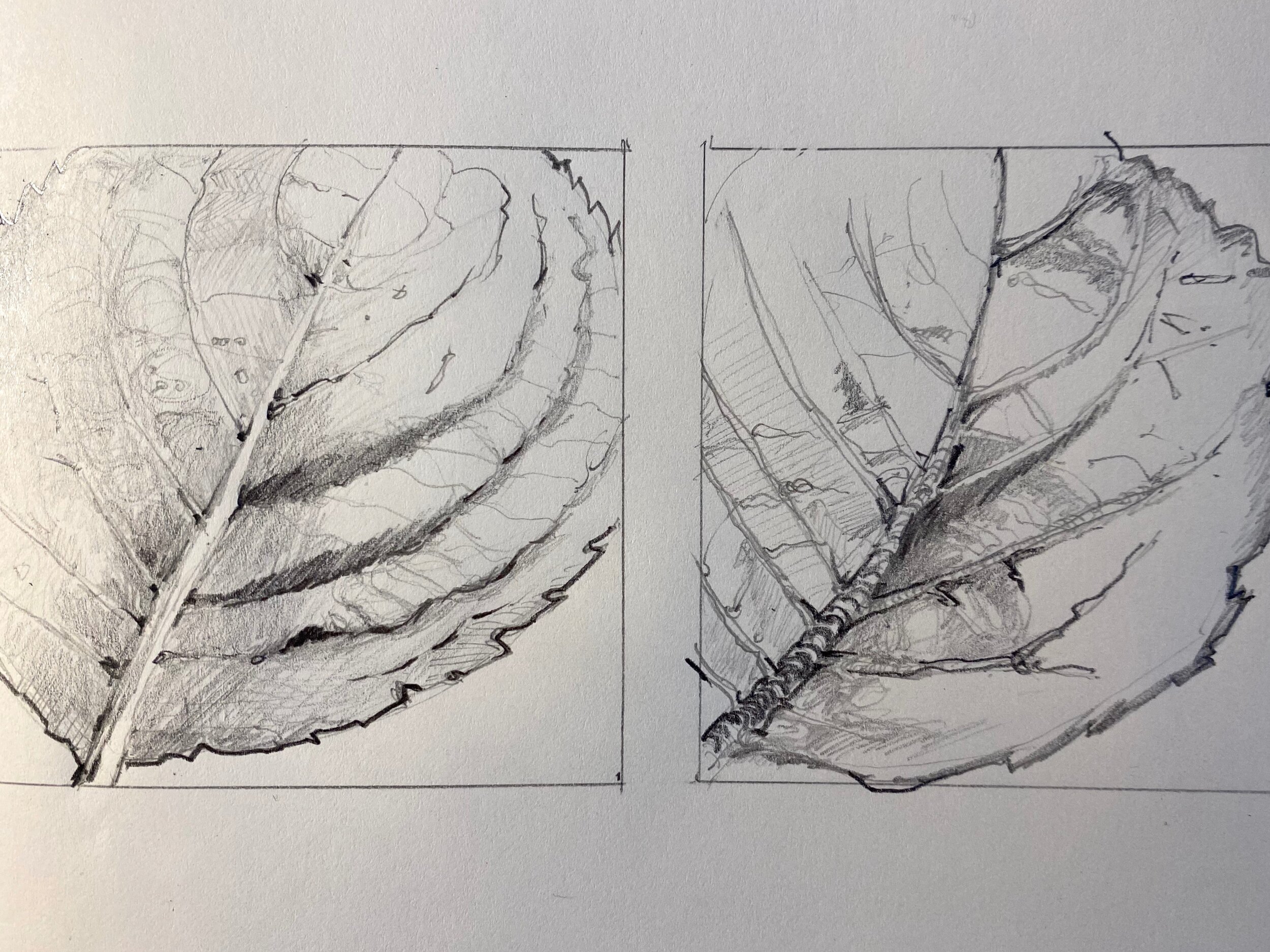

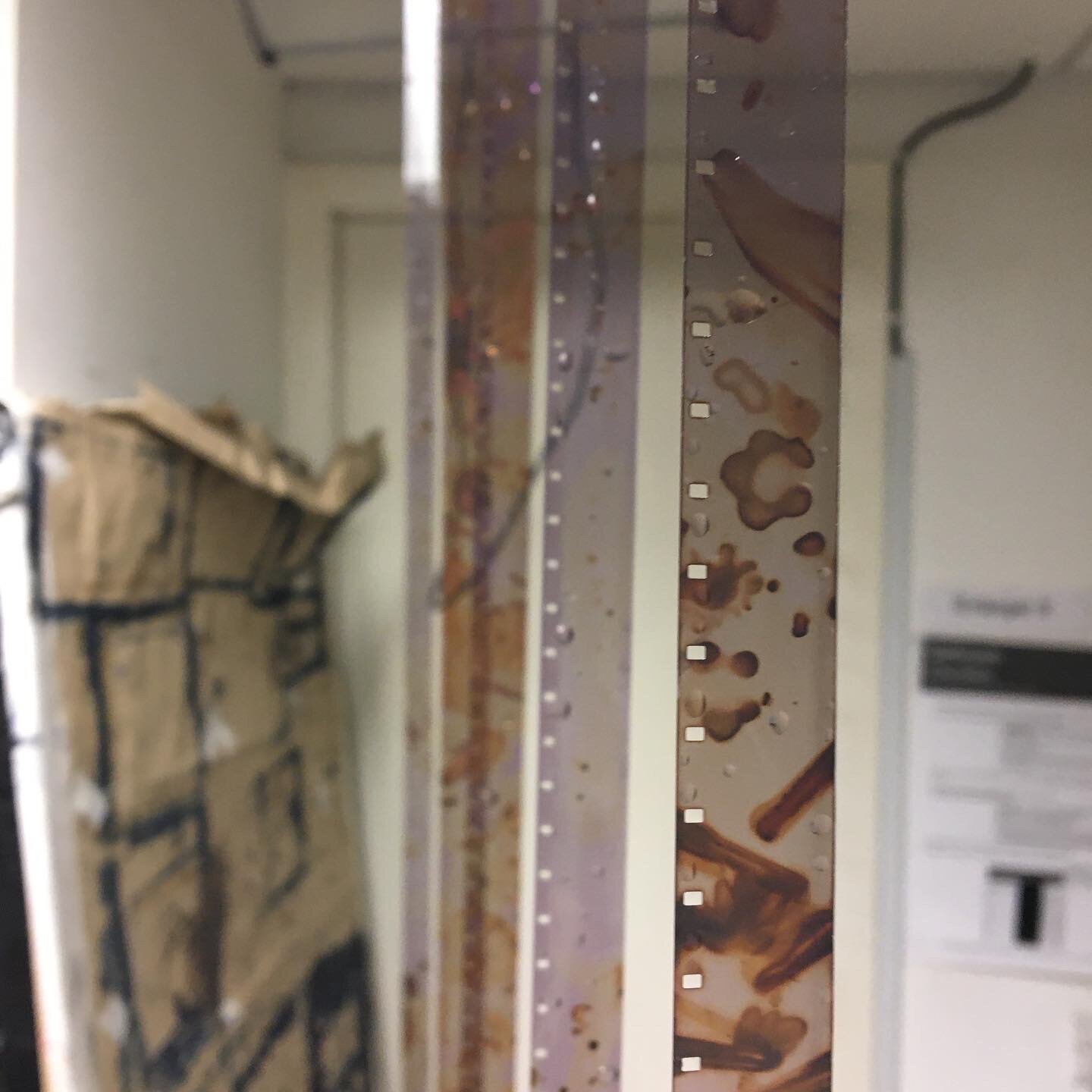

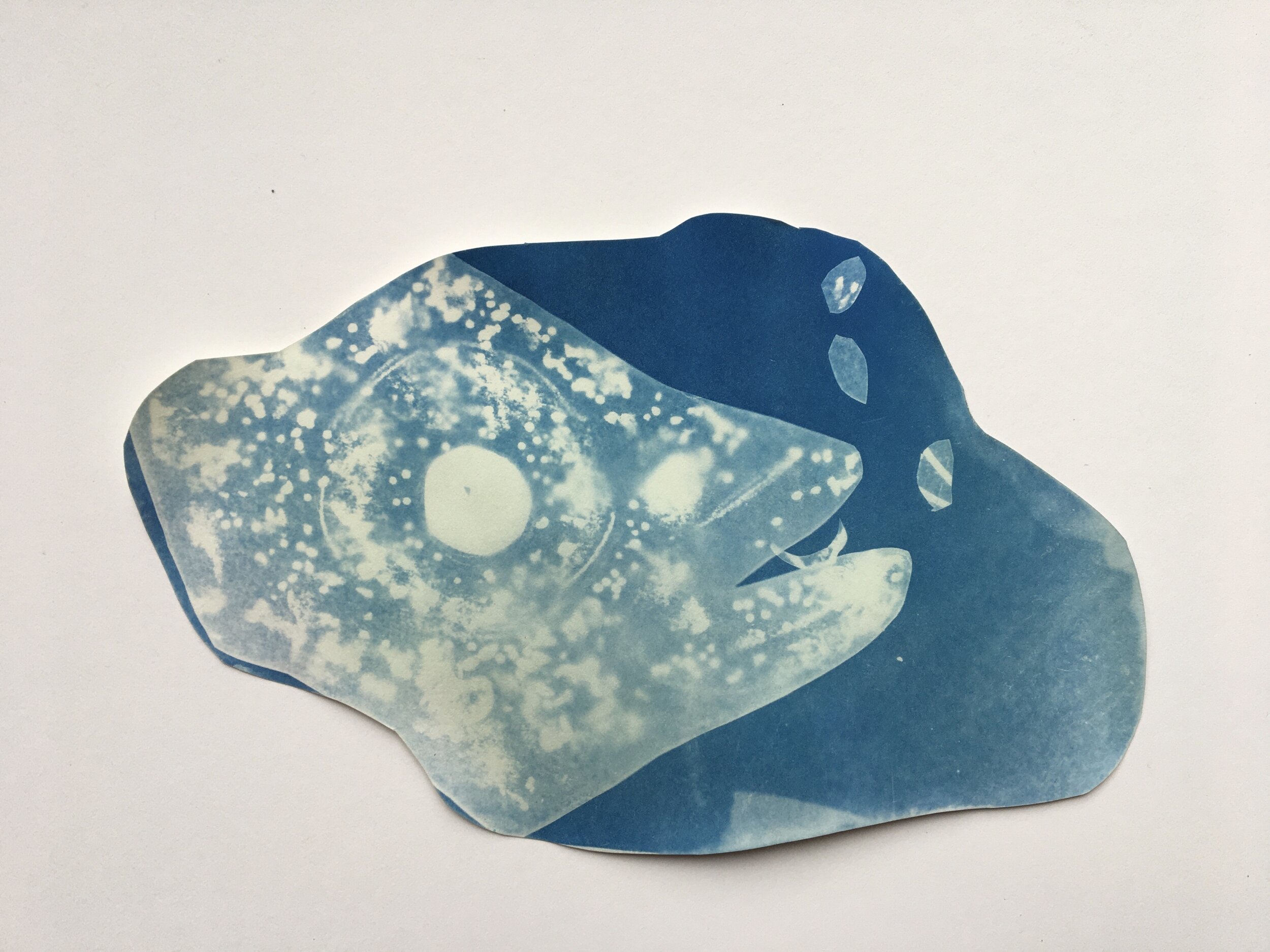

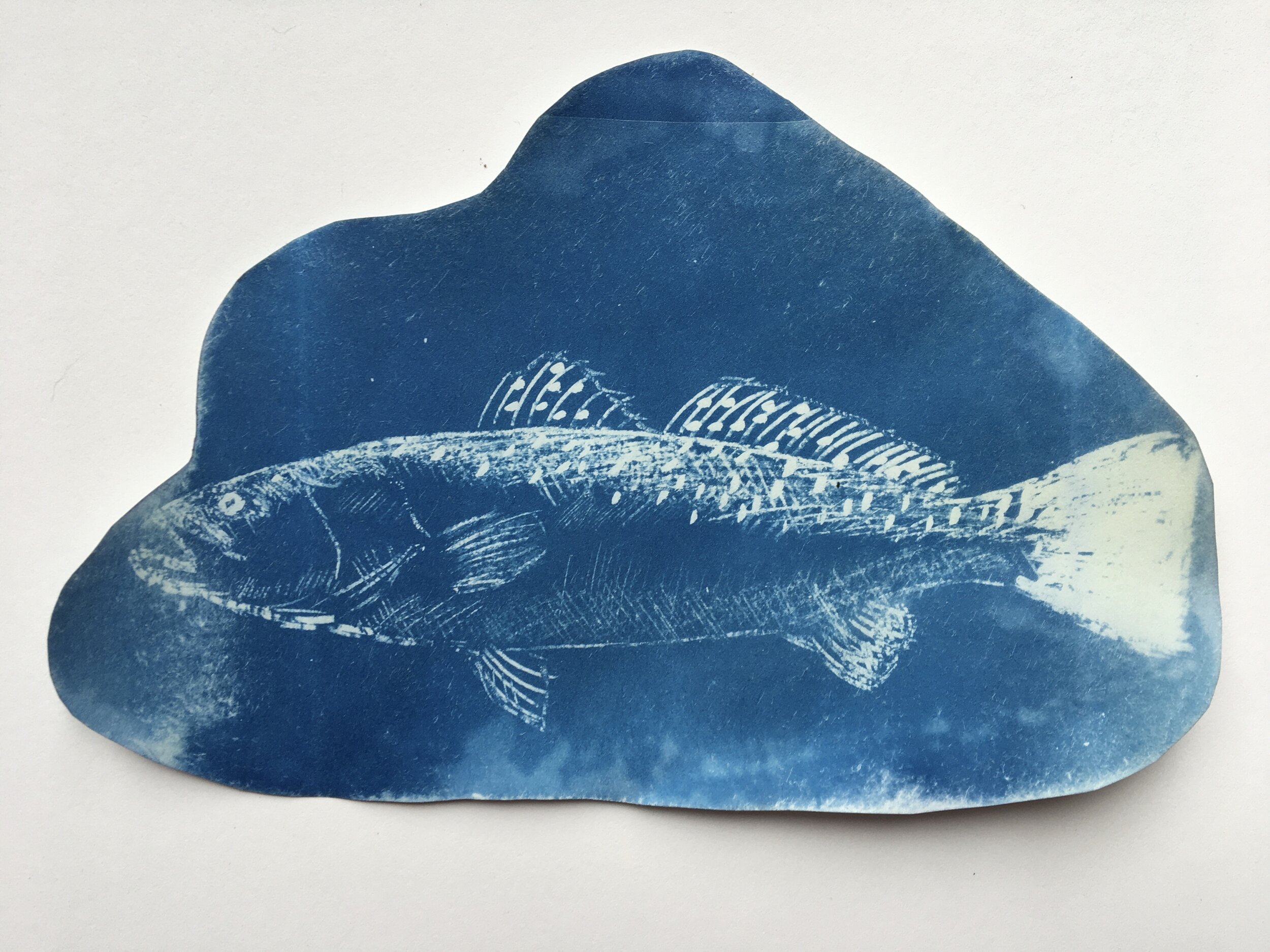

As part of our work together Lydia introduced the idea of creating a phytogram – a 16mm film which is created by layering small pieces of specially prepared plant material onto film strips. Camera-less movie making which beautifully reflects the botanical origin of early celluloid film. To do this many hands are needed and so a workshop was set up, and over the course of a day a group of us gathered together to create the phtytogram. Lydia guides us through the process. First we separate the flowers and plants into their individual parts before soaking them in a solution. The plants are placed onto the film strip and left there to expose for several hours before rinsing and fixing.

We become acutely aware of our hands, of the imprints of our fingerprints which appear on the surface of the film when we touch it. We work with the lightest of touches – pressing petals and leaves onto the film and smoothing them down. The film strips – laid out in long lengths on the table become portraits of a time and place: early spring growth, tiny leaves just newly unfurled; bright petals sneakily picked from a neighbour's garden, a bunch of flowers bought to cheer up a living room, now wrinkled and faded. Precious finds – a perfect piece of seaweed, home-grown mushrooms – are brought in in small plastic tubs and paper bags. We work closely alongside each other, drawn into the miniature scale we are working with.

We plan a screening – a chance to gather to watch the film we have made together. We do not manage to hold this event before lockdown and social isolation comes into effect. The film will wait – a marker of a time in which we could work together side by side, our hands nearly touching.

When I first wrote Celluloid I was interested in how cinemas become a receptacle for stories – both in the films that were screened and in the experiences of cinema goers and workers. All these people gathering together for a shared experience – each and every one of them bringing a unique set of worries, preoccupations, hopes and interests into the auditorium. I think of the cinemas lying empty. I think too of the buildings which used to be cinemas, now adapted into flats and houses. I think of the people inside those houses, carrying on, as best as they can.